Group Dynamics and the Untold Story of Chernobyl

When most people are told to do something by someone in authority, they will obey, even when they are told to do something wrong.

“There was a heavy thud… a couple of seconds later, I felt a wave come through the room. The thick concrete walls were bent like rubber. I thought war had broken out. We started to look for Khodenchuk, but he had been by the pumps and had been vaporised. Steam wrapped around everything; it was dark and there was a horrible hissing noise. There was no ceiling, only sky; a sky full of stars.” (Leatherbarrow, 2016).

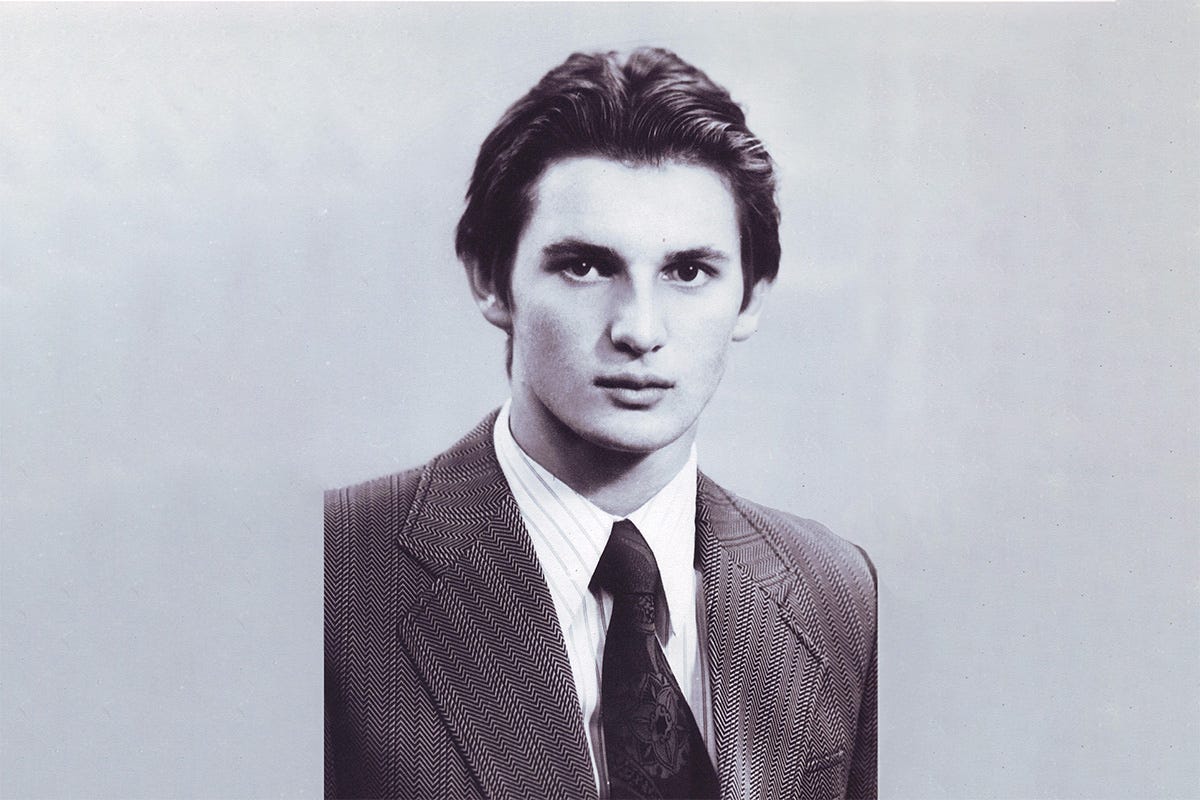

These are the words of Sasha Yuvchenko, a young engineer at Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station, describing what happened on the 26th of April 1986.

Alexandr (Sasha) Yuvchenko

Thirty people, including six firefighters, died as a direct result of the explosion and consequent radiation sickness. A further 60 people died over the coming years from cancer caused by radiation. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that the total number of long-term deaths resulting from Chernobyl will be around 4,000 (WHO, 2006). As well as the fatalities, more than 300,000 people from the area surrounding Chernobyl experienced the upheaval and psychological trauma of being relocated and resettled.

Chernobyl was a disaster waiting to happen. Many at Chernobyl knew this, but few said anything. Those who did were ignored or silenced. Earlier accidents, one at a similar nuclear plant in Leningrad and another at Chernobyl itself, had revealed weaknesses in the reactor design and operation procedures. However, the potential lessons from these accidents were largely covered up or ignored, so as not to upset those higher up in the Soviet pecking order. Engineers at Chernobyl weren’t even aware of the seriousness let alone causes of the Leningrad accident.

Those working in the Soviet nuclear industry were not empowered to speak up when they saw that something had the potential to go wrong.

The global disaster that was Chernobyl was caused by frightened individuals caught up in a group dynamic of denying and avoiding reality, and keeping their head down for fear of punishment. Of course, this reflected the experience of most other Soviet citizens at the time.

The Chernobyl catastrophe is a tragic real-life case study of the psychology of unconscious group dynamics and how these can affect decisions and behaviour in a positive or negative direction. The exact same psycholoical processes are alive and well and are at the root of most problems today.

A group is always more than the sum of the individuals who make up the group. Groups can unleash the potential for great creativity or great destructiveness. People behave differently in a large group compared with when they are alone. Groups generate conformity.

Confirmation bias flourishes in groups. Consequently, groups make more extreme decisions than individuals (in social psychology, this is known as ‘risky shift’). The self-doubt, fearfulness and caution that we all experience is dissolved by the experience of being in a group, just as effectively as it is dissolved by alcohol.

Deviating from normal behaviour in a group

The group culture at Chernobyl was a reflection of the wider political and social culture of the Soviet Union. This culture of never being the one to stand out, speak out or be different from the crowd is chillingly described by Alexander Solzhenitsyn. He tells a darkly comic story in his famous and profound book The Gulag Archipelago:

A district Party conference was under way in Moscow Province. It was presided over by a new secretary of the District Party Committee, replacing one recently arrested. At the conclusion of the conference, a tribute to Comrade Stalin was called for. Of course, everyone stood up (just as everyone had leaped to his feet during the conference at every mention of his name). The small hall echoed with ‘stormy applause, rising to an ovation.’ For three minutes, four minutes, five minutes, the ‘stormy applause, rising to an ovation,’ continued. But palms were getting sore and raised arms were already aching. And the older people were panting from exhaustion. It was becoming insufferably silly even to those who really adored Stalin. However, who would dare be the first to stop?

The secretary of the District Party Committee could have done it. He was standing on the platform, and it was he who had just called for the ovation. But he was a newcomer. He had taken the place of a man who’d been arrested. He was afraid! After all, NKVD men were standing in the hall applauding and watching to see who quit first! And in that obscure, small hall, unknown to the Leader, the applause went on – six, seven, eight minutes! They were done for! Their goose was cooked! They couldn’t stop now till they collapsed with heart attacks! At the rear of the hall, which was crowded, they could of course cheat a bit, clap less frequently, less vigorously, not so eagerly – but up there with the praesidium where everyone could see them?

The director of the local paper factory, an independent and strong-minded man, stood with the praesidium. Aware of all the falsity and all the impossibility of the situation, he still kept on applauding! Nine minutes! Ten! In anguish he watched the secretary of the District Party Committee, but the latter dared not stop. Insanity! To the last man! With make-believe enthusiasm on their faces, looking at each other with faint hope, the district leaders were just going to go on and on applauding till they fell where they stood, till they were carried out of the hall on stretchers! And even then those who were left would not falter...

Then, after eleven minutes, the director of the paper factory assumed a businesslike expression and sat down in his seat. And, oh, a miracle took place! Where had the universal, uninhibited, indescribable enthusiasm gone? To a man, everyone else stopped dead and sat down. They had been saved! The squirrel had been smart enough to jump off his revolving wheel.

That, however, was how they discovered who the independent people were. And that was how they went about eliminating them. That same night the factory director was arrested. They easily pasted ten years on him on the pretext of something quite different. But after he had signed Form 206, the final document of the interrogation, his interrogator reminded him: ‘Don’t ever be the first to stop applauding!’ (Solzhenitsyn, 2003)

These are terrifying examples of how being in a group changes normal behaviour. Speaking out at Chernobyl, raising concerns, would have been a bit like being the first to stop applauding Comrade Stalin at the party conference. If you were to behave differently than the crowd then you would be ‘punished’ in one way or another.

What is the modern equivalent of being the first to stop clapping?

What is the modern equivalent of a Siberian gulag?

Human beings tend to conform to group pressure and to authority even in situations where there is no obvious political repression. Our tendency to obey those in authority and conform to the behaviour of the group that we are a part of is deeply ingrained and unconscious.

So how exactly does being in a group influence individual behaviour?

The Asche conformity study

Imagine for a moment you are a psychology student in 1950s America. You are asked to take part in an experiment on human vision. You agree, and eventually find yourself sitting in a classroom with nine other participants. The experimenter shows you a piece of paper with several lines on it. Your task is simple: look at a comparison line on the left and then look at three other lines, labelled A, B and C, all of which are different lengths, and say which of those are the same length as the comparison line. It looks easy – it’s obviously line B.

The experimenter then goes around the group asking which of the three lines is the same length as the comparison line and, as expected, everybody answers B.

This is repeated a couple of times with different pieces of paper. But on the third time around, something weird happens. The obvious answer is line C, but as the experimenter goes around asking people for their answer, everybody responds with B. That’s just ridiculous; line B is much shorter than the comparison line – it’s obvious. Then the experimenter comes to you and asks which line is the same length as a comparison line. What would you answer? By this time, eight other people have answered B. What do you say? Do you stick to your guns and say C, or do you begin to doubt yourself? In the end, you think, ‘Well, eight people think the right answer is B. They can’t all be wrong.’ So you answer B.

If that had been you, back in the 1950s, you would have been taking part in one of Solomon Asche’s now famous social psychology experiments on group conformity. Asche was interested in the power of groups to disable independent thought. He’d observed that people would often suppress their true opinion or feelings about the topic being discussed just in order to fit in with everybody else in a group. Asche came up with the ‘vision test’ to investigate this phenomenon. What you wouldn’t have known had you been a student in the experiment was that all the other ‘participants’ in the room were actually colleagues of Asche who had been briefed to answer the questions in a particular way. They were told to answer correctly for a number of trials, but on the third trial give the same incorrect answer. The only person being experimented on was you! Asche wasn’t interested in ‘human vision’, he was interested in whether you would go as far as to deny the evidence of your own senses in order to conform with the group. His results were surprising and fascinating. He found that about three quarters of all the participants chose to conform with the group rather than give the correct answer (Asche, 1956).

It’s worth taking a moment to reflect on this. Three quarters of the people would rather deny the evidence of their own senses and consciously say something that they knew to be incorrect in order to fit in with a group. It’s also interesting that the group that they wanted to fit in with was a group of strangers – people they would never see again and who probably meant very little to them. The desire to conform is so powerful, then, that you’ll even do so with people you will never see again.

Just imagine how much more powerful this effect is if you are in a group of people who are important to you. A group of friends and colleagues whom you like and respect, or people who have power over your life in some way – who might decide whether you get a promotion, for example. Or a group you desperately want to be part of.

We like to think of ourselves as autonomous individuals who make free choices, but we all greatly underestimate how much we are influenced and how much our decisions are constrained by the social context that surrounds us.

These psychological processes were present in the Jimmy Savile and BBC child abuse scandal, the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico and the VW emissions scandal of 2015. A whole book could be written about the evil of the child sexual abuse perpetrated and covered up in the Roman Catholic Church.

These terrible events had one thing in common. While the wrongdoing (the evil) was being perpetrated, most people in the organisation, including leaders and senior managers, were aware of what was going on but decided to turn a blind eye. When some did raise concerns they were ignored or told to be quiet by people higher up in the pecking order.

When most people are told to do something by someone in authority, they will obey, even when they are told to do something wrong. Similarly, when put under pressure by their peers to do something wrong (or in the case of the Asche experiments, contradict the evidence of their own eyes), most people will conform. Remember, as Rollo May wrote:

the opposite of courage in society is not cowardice; it is conformity (May, 1953).

This is a profoundly true statement.

One of the biggest challenges for leaders today is how to create a culture where people feel safe to speak out when they see wrongdoing (or even evil) in the organisations in which they work. As we have seen, this is not an easy or straightforward task.

There is an old Native American saying that goes something like this: ‘If you don’t hear the whispers, you will soon hear the screams.’

Like with anything, the best place to start in this process is with yourself. It’s very easy to criticise people who are ‘out there’ without first looking at your own internal saboteur. Carl Jung wrote:

“The acceptance of oneself is the essence of the whole moral problem and the epitome of a whole outlook on life. That I feed the hungry, that I forgive an insult, that I love my enemy in the name of Christ – all these are undoubtedly great virtues. What I do unto the least of my brethren, that I do unto Christ. But what if I should discover that the least among them all, the poorest of all the beggars, the most impudent of all the offenders, the very enemy himself – that these are within me, and that I myself stand in need of the alms of my own kindness – that I myself am the enemy who must be loved – what then?” (Jung, 1963) my emphasis

Begin by recognising and understanding your own vulnerability to turning a blind eye to evil. Jung called this your shadow. All of the ‘actors’ in the dramas of evil that I’ve described in this chapter were not, for the most part, evil people. They were people who were caught up in a system that brought out and nurtured their potential for evil – their saboteur. To paraphrase Philip Zimbardo, they weren’t ‘bad apples’, they were simply apples in a ‘rotten barrel’. And like all apples, they had the potential to go bad.

Think about you and your organisation. Do people feel safe to speak up if they see wrongdoing? If not, why not?

References

Asch, S. E. (1956). ‘Studies of Independence and Conformity: I. A Minority of One against a Unanimous Majority’. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 70(9), 1–70.

Jung, C. G. (1963). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. London: Vintage.

Leatherbarrow, A. (2016). Chernobyl 01: 23:40: The Incredible True Story of the World’s Worst Nuclear Disaster. London: Andrew Leatherbarrow.

May, R. (1953). Man’s Search for Himself. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Solzhenitsyn, A. I. (2003). The Gulag Archipelago, 1918–56: An Experiment in Literary Investigation. New York: Random House.

World Health Organization (2006). Health Effects of the Chernobyl Accident and Special Health Care Programmes. Report of the UN Chernobyl Forum Expert Group ‘Health’. Geneva: World Health Organization.